The $1.3M Typo: A Developer's Guide to Payment Claim Precision After Iris v Descon

- John Merlo

- Dec 2, 2025

- 14 min read

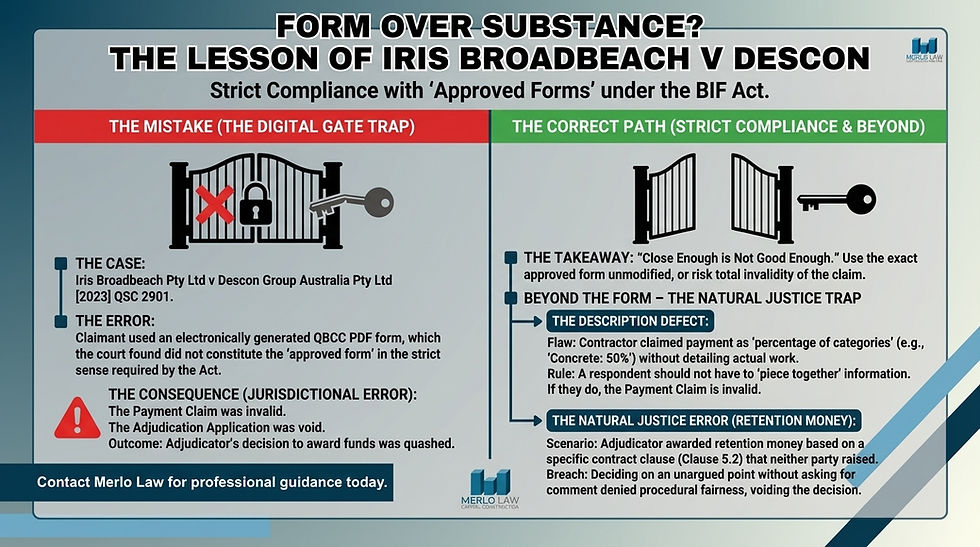

In the high-stakes world of Queensland property development, profit margins are won and lost on precision—in planning, in execution, and, most critically, in paperwork. A recent court decision, Iris v Descon, sent a shockwave through the industry by invalidating a $1.3 million payment claim not because the work wasn't done, but because of a fundamental procedural error. This case is more than a legal precedent; it's a stark business lesson on the immense financial risk of non-compliance with Queensland's security of payment laws.

This article deconstructs this case not as a legal report, but as a business process failure. We will reverse-engineer the exact mistakes made and provide a concrete playbook—a set of "Digital Rules of Engagement"—to ensure your projects are never exposed to the same vulnerability. For developers, this isn't about legal minutiae; it's about robust financial risk management.

Key Takeaways

Procedural Errors Invalidate Claims: The Iris v Descon case proves that even minor procedural mistakes, like failing to properly identify the construction work, can render a multi-million dollar payment claim invalid under the BIF Act.

The BIF Act is Unforgiving: Queensland's security of payment legislation demands strict compliance. Adjudicators have no discretion to overlook errors in how a payment claim is formulated and served.

Systemisation is Your Best Defence: Developers must implement a rigorous, systemised approach—a "Digital Rule of Engagement"—for managing all payment claims and responses to mitigate significant financial risk.

Adjudication is Rapid: The QBCC refers nearly all adjudication applications within four business days, meaning developers have a very short window to prepare a robust response.

Deconstructing a $1.3M Procedural Failure: The Iris v Descon Case

What Exactly Went Wrong for Descon?

The factual background of the Iris v Descon case is a cautionary tale of how a simple procedural error can have multi-million dollar consequences in construction law. Descon Group (Aust) Pty Ltd submitted a payment claim for over $1.3 million to Iris CC Pty Ltd for work on a project. The core issue that unravelled their claim was its failure to adequately identify the specific construction work it related to, a strict requirement mandated by the Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017 (BIF Act).

The claim was found to be vague, lacking the necessary detail to connect the amount claimed with the specific work performed under the contract. The court determined this was not a minor clerical error that could be overlooked; it was a substantive failure that made it impossible for the developer, Iris, and subsequently an adjudicator, to properly assess the claim against the contract's terms and the work actually completed.

The Court's Rationale: Why Precision is Non-Negotiable

The Supreme Court's reasoning was clear and firm, reinforcing the unforgiving nature of the BIF Act. The court explained that the Act's strict requirements are not arbitrary red tape; they exist to ensure a fair, transparent, and rapid adjudication process. The entire "security of payment" framework hinges on the respondent's ability to understand precisely what they are being asked to pay for. If a payment claim is vague or poorly defined, the recipient cannot formulate a meaningful and detailed response in their payment schedule.

This ambiguity fundamentally undermines the system's objective of facilitating cash flow and resolving disputes quickly. The court confirmed that an adjudicator has no jurisdiction or power to rule on a claim that was invalid from the very outset due to such a procedural error.

The Financial Aftermath and the Business Lesson

Imagine the moment the executive at Descon received the news. Their $1.3 million claim, representing significant work and outlay, was now void. The issue wasn't the quality of the construction or a dispute over the value of the work itself, but a flaw in their invoicing and administrative process. The immediate outcome is a significant, potentially catastrophic, impact on cash flow, project profitability, and the company's financial stability.

The business lesson from this scenario is stark: administrative and legal compliance is as critical to a project's success as the physical construction itself. This was not just a legal loss; it was a systemic business process failure that highlights the need for absolute precision in every document submitted under the BIF Act.

Understanding Your Core Obligations Under the BIF Act

The Purpose of the BIF Act

The BIF Act is a critical piece of legislation designed to protect cash flow down the entire contracting chain in Queensland's construction industry. Its primary purpose is to enforce a rapid payment and dispute resolution process, ensuring contractors and subcontractors are paid on time. The Act establishes a statutory framework built around two key documents: the "payment claim," which acts as a formal demand for payment, and the "payment schedule," which is the developer's or head contractor's formal response. It is crucial to understand that these documents carry significant legal weight, far beyond a standard invoice or a simple commercial disagreement.

The legal landscape is also continually evolving, with amendments to the Act in 2024 underscoring the need for ongoing diligence from developers. This entire framework is a cornerstone of Queensland’s construction law framework.

What Makes a Payment Claim Valid?

As the Iris v Descon case so powerfully demonstrated, a payment claim must meet several essential requirements under Section 68 of the BIF Act to be considered valid. First, it must be in writing and correctly addressed to the respondent (the party liable to pay). It must clearly state the amount of the progress payment being claimed. Most critically, the claim must "identify the construction work or related goods and services to which the progress payment relates."

This means providing enough detail for the respondent to understand exactly what work the claim covers. Finally, to gain the full protection and power of the Act, the document must explicitly state that it is a payment claim made under the Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017. Without this endorsement, it may be treated as a simple invoice, lacking the Act's powerful enforcement mechanisms.

The Critical Role of the Payment Schedule

Warning: The payment schedule is a developer's most critical tool for managing payment disputes. Failing to provide a detailed payment schedule within the strict statutory timeframe can result in a legal obligation to pay the entire claimed amount, regardless of its actual merit.

This is not an exaggeration. If a developer fails to respond with a valid payment schedule on time, they become liable for the full amount of the claim. The schedule must identify the payment claim it is responding to, state the amount the developer agrees to pay (the "scheduled amount," which can be zero), and, most importantly, provide detailed reasons for withholding any part of the payment. Vague justifications are insufficient. This document is the developer's primary, and sometimes only, opportunity to formally state their case before the matter proceeds to a rapid adjudication.

Given the high stakes and tight deadlines, seeking advice from a building and construction lawyer when formulating a response to a complex or contentious claim is an essential risk management step.

Forging Your Digital Rules of Engagement: A Preventative Playbook

Effective risk management in construction is not about reacting to problems; it's about designing systems that prevent them. The lesson from Iris v Descon is that procedural compliance for payment claims must be treated with the same rigour as structural engineering. A "Digital Rules of Engagement" is a systemised, technology-enabled playbook that standardises how your organisation receives, assesses, and responds to every payment claim, ensuring you meet your statutory obligations every time. This is a fundamental component of modern construction management.

Rule 1: Centralise and Standardise All Incoming Claims

The first point of failure in managing a payment claim is often the most basic: not knowing you've received it or who is responsible for it. To eliminate this risk, the first step is to establish a single, dedicated email address (e.g., claims@developer.com.au) or a specific portal for the official receipt of all payment claims. This must be clearly stipulated in every subcontractor agreement and contract. This centralisation prevents claims from getting lost in individual project managers' inboxes.

The next step is to implement a standardised intake checklist for administrative staff who monitor this channel. This simple checklist should be a non-negotiable first step for every document received. It verifies that the incoming claim meets the basic statutory requirements of the BIF Act: Does it state it's a BIF Act claim? Does it clearly identify the work and the amount claimed? Is it addressed to the correct legal entity?

Any claim that fails this initial check is immediately flagged and escalated for legal or senior management review before the clock on the response deadline even starts.

Rule 2: Mandate a "Two-Person Review" for All Payment Schedules

Issuing a payment schedule is a significant legal and financial act. Relying on a single project manager, who may be under immense time pressure, to carry this responsibility alone is a major risk. A mandatory "two-person review" process for every payment schedule before it is issued is a powerful safeguard. This system involves a partnership: one person from project management, who has the on-the-ground knowledge to verify the work completed and identify any defects, and one person from finance, legal, or contract administration, who understands the commercial and statutory obligations.

This dual-review process ensures that any reasons for non-payment are not just technically accurate but also contractually sound. The review cross-references the proposed deductions with the specific terms of the construction contract, ensuring the justification is robust enough to withstand an adjudicator's scrutiny.

Rule 3: Develop a "Reasons for Non-Payment" Library

I often see a project manager, under pressure to meet a deadline, write a vague reason for withholding payment like "work incomplete" or "defective work." In an adjudication, this is almost useless. An adjudicator needs specifics. They need to see a clear link between the amount you're withholding and a contractual right to do so. This is where a pre-approved "Reasons for Non-Payment" Library becomes an invaluable tool. Instead of improvising, the project manager can select a detailed, contractually-grounded reason from a dropdown menu.

For example, they can select a template that reads: "Withholding $50,000 as per Clause 14.2 of the contract due to non-compliance with specified material standards for Stage 3 waterproofing, as documented in Site Report XYZ dated [Date]." This simple system transforms a vague, indefensible dispute into a precise, evidence-based position that an adjudicator can understand and accept. It professionalises the entire process and is a key part of the risk management services offered by Merlo Law’s construction law practice.

Rule 4: Integrate Calendar Alerts for BIF Act Deadlines

The BIF Act's deadlines are absolute. Missing one by even a few hours can result in a default liability for the full claimed amount. Relying on manual reminders or memory is a recipe for disaster.

The solution is to create an automated workflow that triggers the moment a valid payment claim is logged in your central system.

Step 1: The claim's receipt date is entered into a central project management or accounting system.

Step 2: The system, pre-programmed with the BIF Act's statutory timeframes, automatically calculates the final deadline for the payment schedule to be served.

Step 3: This deadline is then used to automatically populate the calendars of the responsible project manager, the contract administrator, and in-house legal counsel with a series of escalating reminders (e.g., "7 days to deadline," "3 days to deadline," "24 hours to deadline").

This simple automation removes the risk of human error and ensures that a critical, legally binding deadline is never overlooked.

Responding When a Payment Claim Lands on Your Desk

Your First 24 Hours: Triage and Assessment

The moment a payment claim arrives, the clock starts ticking. Your response in the first 24 hours is critical for setting up a successful defence against any potential payment dispute. The process should be immediate and systematic.

Step 1 is the initial validation check. The administrator receiving the claim uses the standardised intake checklist to confirm it meets the BIF Act's basic requirements.

Step 2 is immediate distribution. The validated claim is forwarded to the relevant project manager for a technical assessment of the work claimed versus the work completed.

Step 3 is scheduling and flagging. The statutory deadline is immediately calculated and entered into the calendar alert system, and an internal meeting is scheduled between the project manager and the second reviewer to formulate the payment schedule well in advance of the deadline.

This triage process ensures no time is wasted and all key personnel are alerted to the progress payment claim.

Crafting a Defensible Payment Schedule

The strength of your position in an adjudication rests almost entirely on the quality of your payment schedule. When withholding payment, every reason must be specific, objective, and defensible. Vague statements will be dismissed by an adjudicator. You must link each deduction directly to evidence, such as a clause in the contract, a formal site instruction, a non-conformance report, or photographic evidence of defects.

For instance, contrast a weak reason like "poor quality work" with a strong, defensible reason: "Deduction of $25,000 for the full cost of rectification of the defective concrete pour on Grid Line 5, which failed to meet the specified 32MPa strength requirement as per the independent engineer's report dated 15/11/25, a copy of which is attached." This level of detail is non-negotiable.

For complex claims involving multiple issues, this is precisely where you need expert guidance on payment claim disputes.

Understanding the Adjudication Process

It is crucial for developers to understand that adjudication is not a court hearing; it is a rapid, "on the papers" process designed for speed. Once a claimant files an adjudication application, the timeline becomes extremely compressed. The Queensland Building and Construction Commission (QBCC) is responsible for referring these applications, and their statistics show an incredibly fast turnaround: the QBCC refers 100% of applications to an adjudicator within 4 business days. This means a developer has a very short window to prepare and submit their adjudication response. There are no hearings, no cross-examinations of witnesses, and no time for extensive investigation.

The adjudicator's decision will be based almost solely on the content of the payment claim, the detail in the payment schedule, and the written submissions and evidence provided by both parties. If your justification isn't clearly articulated and evidenced in your payment schedule, you have likely already lost.

Navigating this high-pressure process can be daunting, and the support of a specialist QBCC lawyer can be invaluable.

What Happens if an Adjudicator's Decision is Flawed?

The Limited Grounds for Appeal

Warning: An adjudicator's decision under the BIF Act is binding and enforceable as a judgment debt, even if they make a clear error of fact or law. The path to challenging a decision is narrow and complex.

Many developers are shocked to learn that you cannot simply appeal an adjudicator's decision because you disagree with it or believe they interpreted the contract incorrectly. The only grounds for challenging a decision in court are for "jurisdictional error." In simple terms, this means the adjudicator acted outside their legal power or authority.

Examples of jurisdictional error include deciding on a claim that was invalid from the start (as was the central issue in the Iris v Descon case), failing to provide natural justice to a party (e.g., not considering their submission at all), or making a decision on matters not covered by the construction contract.

Proving jurisdictional error is a high legal bar to clear and requires a sophisticated legal argument; it is not a simple re-hearing of the facts.

The Role of QCAT and the Courts

The process for a developer who believes an adjudication decision is infected by jurisdictional error is not a straightforward appeal. The correct legal venue is the Supreme Court of Queensland, where an application must be filed to have the decision declared void and set aside.

This is a formal litigation process. It's important to distinguish this from the role of the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT). QCAT is the primary venue for reviewing many administrative decisions made by the QBCC under the Queensland Building and Construction Commission Act 1991, such as licensing disputes or disciplinary actions. While a small percentage of QBCC decisions are set aside at QCAT (4.7% in Q3 2023-24), this is a separate stream from challenging an adjudicator's BIF Act decision.

Understanding the correct legal venue for each type of dispute is critical, and the process of appealing the decision at QCAT or launching a Supreme Court challenge requires specialist legal advice.

Is Litigation the Right Path?

Expert Insight: Litigation to challenge an adjudicator's decision should always be a carefully considered final option, not a knee-jerk reaction. The core claim in court is not about the merits of the payment dispute itself, but about the legality of the adjudicator's process.

Challenging an adjudicator's decision is a complex, costly, and time-consuming exercise. A developer must undertake a thorough cost-benefit analysis before proceeding. This involves weighing the amount of money in dispute against the high probability of significant legal fees and the diversion of senior management's time and focus. Even if successful, the original payment dispute may still need to be resolved through other means.

The decision to initiate a Supreme Court application is a strategic one that should only be made after a realistic assessment of the likelihood of success and the potential financial outcomes. Our construction litigation team can provide a frank assessment to help you make this critical decision.

Conclusion: Shifting from Reactive Defence to Proactive Process

The $1.3 million lesson from Iris v Descon is not that the law is complicated, but that business processes must be robust enough to meet its strict requirements. For Queensland property developers, the BIF Act is not a legal hurdle to be dealt with only when a dispute arises; it is an operational framework that must be embedded into your project management DNA.

By implementing a clear set of "Digital Rules of Engagement"—centralising claims, mandating reviews, using reason libraries, and automating deadlines—you shift from a reactive, defensive posture to one of proactive control. This systemisation minimises risk, protects cash flow, and ultimately insulates your projects from costly, and entirely preventable, procedural failures.

For more insights into construction law and risk management, please see our other legal publications.

FAQs

What is the single biggest mistake a developer can make when receiving a BIF Act payment claim?

The single biggest mistake is failing to serve a detailed payment schedule within the strict statutory timeframe. If you miss the deadline, you become legally liable for the entire amount claimed, regardless of whether the claim is inflated, inaccurate, or even fraudulent. A close second is serving a schedule on time but with vague reasons for withholding payment (e.g., "defective work"), which an adjudicator will likely disregard.

Can I include a claim for damages (e.g., for project delays) in my payment schedule?

Yes, you must include all contractual set-offs, including liquidated damages, in your payment schedule if you intend to rely on them as reasons for withholding payment. Under section 69 of the BIF Act, a payment schedule must state all reasons why the scheduled amount is less than the claimed amount.

This includes:

• Defective, incomplete, or non-compliant work

• Contractual set-offs for liquidated damages due to project delays

• Other contractual deductions you are entitled to under the construction contract

Critical warning: Under section 82(4) of the BIF Act, you cannot raise "new reasons" for withholding payment in an adjudication response if those reasons were not included in your payment schedule. If you fail to include a contractual set-off (such as liquidated damages) in your payment schedule, you will be precluded from relying on that set-off during adjudication, even if you are contractually entitled to it.

The payment schedule is not limited to work quality issues—it must capture all contractual grounds for withholding payment. However, these must be genuine contractual entitlements, properly calculated, and clearly documented with supporting evidence (such as delay analysis or defects reports). The adjudicator will assess whether your claimed set-offs are valid under the contract.

What happens if I pay the adjudicated amount but still believe the decision was wrong?

Paying the adjudicated amount is a legal requirement to avoid further enforcement action, but it does not extinguish your contractual rights. You can still pursue the matter through the courts to seek a final determination of the dispute. This is often referred to as "paying now, arguing later." The payment made under the adjudication is considered an interim payment, and a court can later make a final ruling that requires the money to be repaid if it finds in your favour.

How do the 2024 amendments to the BIF Act affect developers?

The 2024 amendments introduced several changes, including modifications to how trust accounts are managed and enhanced powers for the QBCC. For developers, a key takeaway is the continued legislative focus on ensuring timely payments and increasing transparency. It reinforces the need for meticulous record-keeping and strict adherence to all procedural requirements, as the regulatory environment is becoming more, not less, stringent.

Is an email sufficient to serve a payment claim or payment schedule?

Yes, provided the contract allows for service by electronic means. Most modern construction contracts specify email as an acceptable method for serving notices. It is crucial to ensure you are sending it to the correct, contractually nominated email address and that you can prove it was sent (e.g., by keeping a sent record). If the contract is silent on electronic service, it is best practice to serve the document both by email and by a method specified in the Act, such as post or in person, to avoid any dispute over valid service.

This guide is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For advice tailored to your specific circumstances, please contact Merlo Law.

Comments